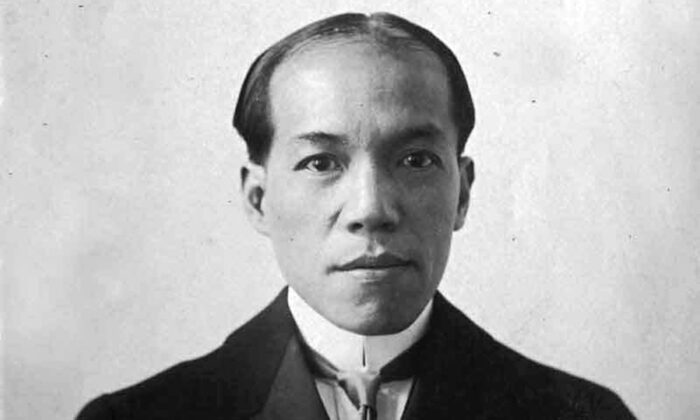

Portrait of Liang Qichao in 1910. (minguotupian.com/Public domain)

China: A Constitutional Monarchy

China today could be as much under the rule of law and as free as Hong Kong was guaranteed to remain under the 1997 Joint Declaration.

It could also be enjoying the institutions of representative democracy that the British normally gave to their colonies but did not give to Hong Kong, no doubt out of fear this would provoke the wrath of the communists.

The British were probably right to have been prudent; the communists would never have accepted the example of an increasingly democratic Chinese entity on their doorstep. This would have proved a far too attractive alternative.

A Successful Model

Of all constitutional models that have been exported to the world, constitutional monarchy has proved remarkably successful across a range of cultures. Apart from the UK and 15 other Commonwealth realms, including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, there are a swathe of countries across Europe that are constitutional monarchies, as well as countries such as Jordan and Morocco. Then there are countries that were once constitutional monarchies in what seniors often recall as a golden age, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, and to a lesser degree, Egypt and Libya.

Apart from offering a proven form of government that works well and that unleashes wealth without diminishing freedom, constitutional monarchy can be especially consistent with societies based on traditional values, and especially where some form of monarchy is already a national institution. As such, it may well already be a center of interest, tradition, and of national unity.

The fact today is that, by any measure, constitutional monarchies are disproportionately found among those countries that enjoy the highest standard of living, the longest life expectancy, and the best education, as well as being the freest. Of course, it’s not that sound republics cannot similarly prosper—Switzerland being a classic example to say nothing of the United States—but being a republic as such is no guarantee of success.

Over many centuries, England was more inclined against absolute monarchical rule than most. The proposition that the king was not absolute but under the law emerged even before the Magna Carta. The 17th struggle between Parliament and the king led to civil war, the trial and execution of the king, the emergence of a republic, a restoration, and finally—in the Glorious or Bloodless Revolution of 1688—constitutional monarchy Mark 1.

This brought those checks and balances that are the antidote to Lord Acton’s timeless warning, “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Without so designing it, Montesquieu saw that it incorporated for the first time the separation of the three powers, executive, legislative, and judicial.

As the Anglo-American scholars Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have persuasively argued, probably the most important factor in national success is in having sound institutions. If ever this has been well demonstrated, it has been in the domination of the world over the last 300 years by the Anglo-Americans.

We are now frequently told that by adopting state capitalism without the rule of law on the Hitler and Mussolini models, the Maoists have done wonders, lifting millions of Chinese people out of poverty. But this was after decades of imposed poverty, a reign of terror, and the enslavement and the killing of millions. The system continues as an increasingly harsh dictatorship through the Chinese Communist Party.

The fact is that, had the mainland long been under the same system as Hong Kong, the per capita income would today be up with rich countries such as Singapore and Hong Kong itself, instead of averaging one fifth of that. In addition, the people would be free and not slaves of the Party.

In this context, it’s fascinating to consider how close China came in the late 19th century to becoming a constitutional monarchy and how different history could have been.

A Different History

Among those calling for developing late 19th century imperial rule into a modern constitutional monarchy were two advisers to the Emperor Guangxu, Liang Qichao and his mentor Kang Youwei. They were behind the Hundred Days of Reform in 1898, which, if they had been entrenched, would have modernized China.

But reactionary elements led by the Dowager Empress Cixi engineered a coup d’état, placing the emperor in seclusion and killing his advisers. Liang and Kang escaped to Japan where they set up a loyalist society, the Baohuang Hui, and campaigned valiantly to set up a Chinese constitutional monarchy.

Liang accepted an invitation to speak in Australia and came just as the six colonies federated into one country. He stayed six months, was received by governors and politicians, and met Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton. He gave lectures both in English and Chinese and was feted wherever he went.

Liang was impressed by the markedly peaceful way in which federation in Australia had been achieved and how closely the people had been involved in the process, both in the election of the constitutional convention, in wide consultations with it, and in the approval of the resulting constitution through referendums in each of the colonies, two in most. All of this was revolutionary, with Liang seeing valuable lessons in this experience for China.

Unfortunately, the forces in the imperial family were too reactionary to allow this development and the new republic too weak for the various forces plotting to take control. Had a Chinese constitutional monarchy survived, history could have been so different. Instead, the monarchy was destroyed and the republic taken over by warlords.

Australia’s Republican Movement

As a footnote, it’s relevant to recall that most major republican movements in Australia have been by people who could be called “fake republicans.” That is, their aim has not been to improve the governance of Australia, but to achieve some ulterior purpose.

In the 19th century, when the British encouraged open immigration, republicans in New South Wales and Victoria wanted to establish a white republic. In the 20th century, the communist party, of no electoral significance but powerful in the unions, planned to establish a soviet-style republic, a dictatorship acting in Stalinist interest

In 1999, when there was a republican referendum, the model would have neutralized the checks and balances vested in the president, who was to replace the governor-general. It would have been the only republic in which the prime minister could dismiss the president without notice, without grounds, and without any right of appeal. The president would have been completely under the control of the prime minister.

Accordingly, the “No” case named the model “the politicians” republic. Despite wide political, media, and celebrity support, this republic was defeated nationally, in every state (a national majority and a majority of states is required), and in 72 percent of federal electorates.

It’s interesting how many prominent proponents of the 1999 republic seem to be supporters of the People’s Republic of China, with, for example, former prime minister and leader of the Australian Labor Party Paul Keating saying in 2017: “That government of theirs has been the best government in the world in the last 30 years. Full stop.’’

[This article appeared in The Epoch Times . It is by Emeritus Professor David Flint AM is a former chairman of the Australian Press Council and Australian Broadcasting Authority. He is the national convenor of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy, the organization which led the “NO” case in the 1999 Australian republic referendum.]