[The reason ACM, alone, has argued so consistently and powerfully that the Governor-General is the Head of State is that not only do our task force of expert constitutional and international lawyers and experts in viceregal practice unanimously assert that this is so.

Far more importantly, this rebuts the false and highly misleading claim by the Australian Republican Movement that only through one of their republican models can we have an Australian as head of state. Moreover, we fear that in any second referendum, the question will deliberately contain this same false and highly misleading claim.

Why?

Because all other claims for this massive change have collapsed from the ridicule they so deservingly attracted.

The following article by Professor David Flint was published in May 2008 in Quadrant. and it centres on his finding of a highly relevant 1907 High Court decision containing the opinions of a bench closely associated with the drafting of the Constitution.

Professor Flint recounts that he could not find the reference where the Court describes the Governor-General in terms of constitutional headship. given that the grant of the executive power direct to him or her was, in 1901, unique in the British Empire.

So he decide to read every case from the foundation of the Court at least while one of the Founders involved in the drafting of the terms of the Constitution was still sitting.

It was in this way that he found what he regards as the treasure of our crowned republic, those obiter dicta, as lawyers say, in that case, R v Governor of South Australia [1907] HCA 31; (1907) 4 CLR 1497 (8 August 1907).

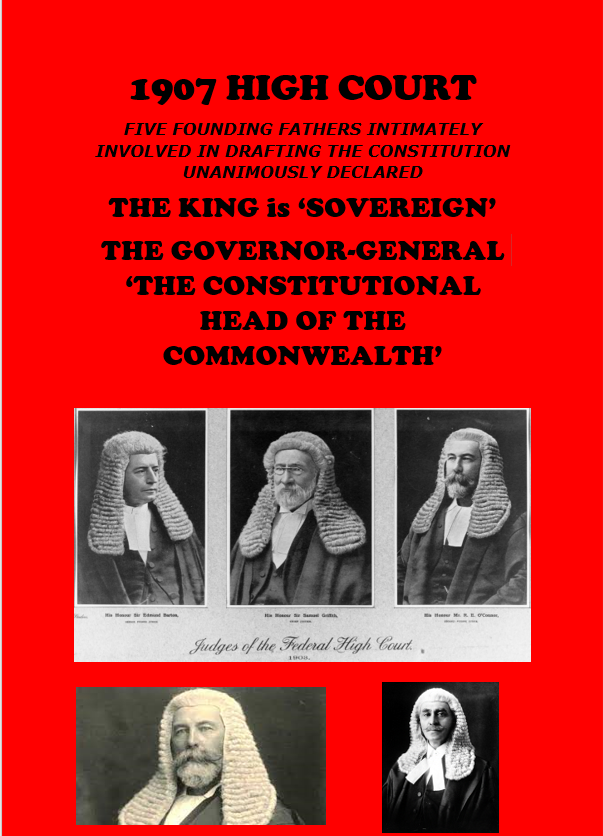

The image above is of the High Court in 1903 at its opening in Melbourne with the three original judges. By 1907 two additional judges had been appointed The details of the judges are in the image below]

The Head of State Debate Resolved

The principal argument advanced in the current campaign for a change to a republic is that the Head of State should be Australian; constitutional monarchists reply that we already have an Australian Head of State in the Governor-General. A hitherto overlooked High Court decision provides the key to the resolution of this dispute.

This campaign is the fourth significant attempt to create an Australian republic. The first was to establish a white racist republic in the nineteenth century, free of the immigration policy of the British Empire. This faded away with the movement to Federation, with the Commonwealth of Australia being endowed with an express power to establish a national immigration policy. The second, and longest campaign, was to create a communist state similar to the East European Peoples’ Republics established after the Second World War. Its proponents never made the slightest impact in Australia electorally, notwithstanding their control of several key strategic unions. The third was initiated by the Australian Republican Movement and promoted by Paul Keating when he was Prime Minister. Its object was to graft onto the constitution a republic, but initially only at the federal level. In this republic, the president would be appointed by parliament. Although a string of implausible reasons for the change were advanced by senior republican figures, ranging from reducing unemployment and the brain drain to stopping Australian expatriates being taken for Britons,[i] the raison d’être of their campaign was that only a republic could provide an Australian Head of State. Their formidable political and media campaign culminated in the 1999 referendum, which was defeated nationally and in all states.The present and fourth campaign for an Australian republic also relies on the same argument about the Head of State. But unlike the last attempt, the republicans are now unable, or more likely, unwilling to specify what sort of republic they propose.[ii]

This is because they remain irreconcilably divided over the form of republic which should be adopted. But they do agree on the issue of the Head of State. They also agree that the process for choosing model and the resulting referendum should be preceded by a plebiscite with no details of the change and only a vague general question about Australia becoming a republic.

Those who favour a republic in which the president would be chosen by the electorate propose a second plebiscite. Those who favour a republic where the president would be chosen by parliament propose other methods of consultation to determine the model. An initial plebiscite is seen by republicans as having at least seven advantages over proceeding immediately to a referendum. First, there will be no need to provide any details whatsoever about the form of republic envisaged. Second, republicans would be united in campaigning for it. Third, voters will not be torn between different forms of the republic. Fourth, the question can be so worded that it will attract the maximum vote without the voters being distracted by any details of precise changes to be made to the Constitution. Sixth, if it passes, people will feel committed to some form of republic in any subsequent referendum. Seventh, if it passes, the constitutional monarchists will be isolated and effectively unable to participate in the debate over the model. The latter will be ensured if there is a second plebiscite where indicating a preference for the existing constitution is not allowed.

There is an eighth advantage for republicans feared by many constitutional monarchists. This is that if the plebiscite were passed, there may be a temptation to try to change the Constitution through the” backdoor.”[iii] This would require all seven parliaments to legislate to amend the Statute of Westminster and then the Constitution, but would no doubt be challenged in the High Court. Constitutional monarchists object in principle to the holding of a vague “blank cheque” plebiscite when the constitution provides the process for popular consultation and decision, a referendum. They say a plebiscite goes against the spirit of the constitution. Moreover it would invite the people to cast a vote of no confidence in one of the world’s most successful constitutions, with the details of the proposed change being kept from them and no guarantee that change would follow. This, constitutional monarchists say, would be a recipe for constitutional instability. They say it is difficult to conceive of a more irresponsible act for the politicians to engage in.[iv]

But let us return to the term, Head of State, on which the republicans have staked so much. In the official 1999 Yes/ No Pamphlet delivered to all households, the Yes case[v] concluded that by saying to each voter that he or she “…will be able to vote YES for the change to an Australian as Head of State or NO to retain the monarchy. If you agree that, as we enter a new century, the time has come for an Australian to be our Head of State, please join with us and help make history on November 6. Vote YES for an Australian republic.”[vi]Constitutional monarchists have long argued that while The Queen of Australia is the Sovereign, and the Governor-General is the Head of State. Accordingly the No case in the 1999 Yes/No pamphlet stated: “Our constitutional Head of State, the Governor-General, is an Australian citizen and has been since 1965.”[vii]

Although the referendum proposal was defeated nationally and in all states, the debate continues. A manifestation of this was in the “Mate for Head of State” campaign in 2006.[viii] Recent research has revealed a High Court decision which is highly relevant to the resolution of this debate.[ix] The decision related to whether the Court could direct the governor in the exercise of his power to fill a vacancy in the Senate.

Under the Australian Constitution the judicial power of the Commonwealth is vested first in the High Court.[x] The High Court is empowered to give final, binding and authoritative decisions concerning the Constitution, so any ruling by the High Court would determine the debate. In addition, this particular bench consisted of some of the most prominent of our Founding Fathers. They surely would have had an excellent understanding of the constitutional intention.

The High Court bench consisted of five judges, all of whom had played significant roles in the political life of Australia, and all of whom had been involved, in different degrees, with the federation of the nation. The Court could be aptly described as a bench of Founding Fathers, such was their grasp of and understanding of the constitutional system of the new Commonwealth of Australia.They were led by the Chief Justice, Sir Samuel Griffith, who had chaired the committee which produced a draft of the Constitution at the 1891 Convention. Of that, those great authorities, Sir John Quick and Sir Robert Garren say that it contained the “whole foundation and framework of the present constitution.”[xi] Then there was Sir Edmund Barton, the first Australian Prime Minister, who was also intimately involved in the drafting of the Constitution and in campaigning for its adoption. He opposed appeals to the Privy Council. I mention this to demonstrate that the bench did not consist of arch conservatives with predictable views.

He and the third justice, Richard O’Connor, were two of the three members of the 1897-1898 Convention drafting committee. O’Connor twice refused a knighthood, an indication again of a less than conservative attitude. (The other member of the drafting committee was Sir John Downer.)The fourth judge was Sir Isaac Isaacs, later our first Australian born Governor-General, who was also closely involved in the movement to Federation and played a significant role in the crucial 1897-1898 convention. His lasting monument is the Engineers Case[xii] of 1920, which established the inexorable, some would also say the regrettable direction of High Court jurisprudence towards the recognition of strong centralist powers in the federal parliament and government. The fifth judge was Henry Bournes Higgins, who like Justice O’Connor, had also refused a knighthood. He was no conservative. It is enlightening to recall his reaction to the introduction of the words in the draft preamble to the Constitution Act, reciting that the people of the several colonies, “humbly relying on the blessings of Almighty God” had decided to unite. He proposed a balancing provision. This was to become section 116 of the Constitution, which prevents the establishment of a national church or the prescription of religious tests. Close to Labor, and made Attorney- General in a Labor government, he is best remembered for the celebrated Harvester judgment which set out the rights of the worker to receive a minimum wage “as a human being in a civilized community.”[xiii] It can be said that all justices had an intimate knowledge of the Constitution and its drafting, in comparative developments in other countries especially the federations, of the workings of the political system and of the role and function of the Crown and its representatives. Both by background and thinking, it was as diverse as any modern court.

The unanimous decision of the Court was read by Sir Edmund Barton. The court held that it had no jurisdiction to direct the Governor concerning the filling of a vacancy in the Senate. For the purposes of the issue under consideration here, what is important is that on several occasions in an admirably succinct judgement, the Court described the Governor of South Australia, and thus all governors, as the “Constitutional Head of State,” or “Head of State”. And the Court declared the Governor-General to be the “Constitutional Head of the Commonwealth.” In some cases this was preceded by the word “officiating,” which seems to be of little relevance in the debate whether Australia should become a republic. The High Court also referred to the King as the “Sovereign,” the term normally used by constitutional monarchists to contrast the role of The Queen with the role of the Governor-General as Head of State.

The case has been referred to in subsequent judgements of the Court on four occasions, that is, in 1981, 1987, 1988 and 1998.[xiv]So almost one hundred years ago, the High Court had thus resolved an acerbic debate which subsequently divided a nation.

The origins of the term head of state

Until recent times the internationally accepted generic term for what is now head of state was “prince.” As the number of republics increase, the term “prince” became less appropriate and the term “head of state” emerged to general acceptance. As an essentially diplomatic term, it usage was accordingly governed by international law and practice.[xv]It was of course impossible to devise a common position description of a head of state because the functions of a head of state range from the purely ceremonial to that of also being head of the government, as in the United States.

The head of state need not even be one person, as the examples of Andorra and Switzerland demonstrate.Under international law, the determination of who is the Head of State is a matter of recognition. The head of state is the person or persons held out to be the Head of the State concerned, and who are recognized as such by other states.The Governor- General’s status in what were then the Dominions was changing significantly as they moved towards full independence. In recognizing that the Dominions and the United Kingdom were “equal in status,” and “in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs,” the Balfour Declaration of 1926 had necessarily to consider the appointment and the status of the Governor-General, who apart from playing the role of a constitutional monarch had until then also represented Imperial interests.[xvi]

The Declaration says the Governor-General is “the representative of the Crown, holding in all essential respects the same position in relation to the administration of public affairs in the Dominion as is held by His Majesty the King in Great Britain…” [xvii]

The clear natural meaning of these words is that diplomatically, the Governor-General, when travelling, is entitled to be held out as and to be received as a Head of State.Perhaps because of the inability or unwillingness of some Australian diplomats to insist on the Governor-General being accepted as Head of State, this has led to at least one diplomatic incident.

In 1987, according to Sir David Smith, the Governor-General, Sir Ninian Stephen, acting on the advice of the Australian Government, cancelled a proposed visit Indonesia because President Suharto had said that he would not be present at the welcome ceremony, but would instead send his Vice-President. The reason advanced was that the Governor-General was not a Head of State. “That year Sir Ninian made State visits to Thailand, China, Malaysia and Singapore,” says Sir David. In each he was received as a Head of State. Soon afterwards, the Indonesian Government admitted that it was wrong, saying that it had been wrongly advised by its officials. The government indicated it would treat our Governor-General as a Head of State on any future visit. This occurred in 1995.[xviii]In 1996, the Commonwealth Government Directory defined the Governor- General’s role in these words, “Function: Under the Constitution the Governor-General is the Head of State in whom the Executive Power of the Commonwealth is vested.”[xix]Since then Governors-General have travelled overseas and been received in all countries as Australian Head of State, at the time of writing most recently in Israel in 2008 when Major-General Jeffery unveiled the monument to honour the celebrated charge by the Australian Light Horse at Beersheba which was of great importance in the Allied campaign against the Central Powers.

The Constitutional Head of State

As a diplomatic term, the words “Head of State” did not appear were not used in constitutions until relatively recently. Somewhat inauspiciously for republican arguments in Australia, the first domestic use seems to have occurred in countries under fascist governments. The first such use seems to have been by Generalissimo Franco who during the vacancy in the Spanish throne became El Jefe del Estado. Then Le Maréchal Philippe Petain became Le Chef d’État in Vichy France.[xx] As to Australia, Sir David Smith in his magisterial work, Head of State,[xxi] has put together a vast amount of material which presents an argument, so far unanswered, that the Governor-General is the constitutional Head of State.

This centres on section 61 of the Constitution which was the first constitution in the British Empire to provide that the Governor- General should exercise the executive power. In other parts of the Empire, this was done by Letters Patent establishing the office and by Instructions from the Sovereign. (The Australian Constitution was also the first to allow for amendment in the Dominion without reference to London.)

Section 61 provides: “The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Queen and is exercisable by the Governor-General as the Queen’s representative, and extends to the execution and maintenance of this Constitution, and of the laws of the Commonwealth.”

In 1975, Buckingham Palace confirmed that the Sovereign cannot and by implication never could review or reverse decisions taken by the Governor-General under section 61.[xxii] The Speaker had asked The Queen to reverse the decision of Sir John Kerr to withdraw the Hon. G. Whitlam’s commission as Prime Minister and to appoint the Leader of the Opposition, the Rt. Hon. Malcolm Fraser.

The Palace responded that as the commissioning power was vested in the Governor-General, it would not be proper for her to intervene in matters so clearly placed within the jurisdiction of the Governor-General under the Constitution.In the book, Sir David anticipates, and in my view refutes arguments which have been advanced against the proposition that the Governor-General is Head of State.One which he revealed to be without foundation was recently revived by one of the prominent delegates appointed by the Federal Government to its 2020 Summit, Professor Robert Manne. A few years ago the former Chief Justice of Australia, republican Sir Anthony Mason, made the same claim, which he now probably regrets.This is that it is a “robust convention” that there is no place for the Governor-General when The Queen is present, thus proving that Her Majesty is the Head of State.[xxiii]

Sir Anthony Mason was, incidentally, also appointed without his knowledge, to sit on the 2020 Summit panel on governance. He declined.[xxiv]He also had previously declared that he became a republican when watching the 1932-1933 bodyline cricket series, but as Sir David Smith observes, he waited 65 years to tell the world, accepting an imperial knighthood on the way.[xxv]

Sir Anthony argued the “robust convention” when he sought, in a paper delivered at the Australian National University, to demolish the argument advanced by Sir David Smith that the Governor General is Head of State. Sir Anthony had dismissed Sir David’s argument as “arrant nonsense.” To demonstrate this, Sir Anthony relied on Sir Zelman Cowen’s absence when the Queen opened the High Court building in Canberra in 1980. Sir David Smith replied that a practice of the Governor-General withdrawing when The Queen was present seemed to have developed on some previous Royal visits to Australia, but he knew of no constitutional or other basis for it. So he took the matter up with Buckingham Palace. He was told that the Palace also knew of no basis for the practice, which seemed to be peculiar to Australia, and that The Queen would be pleased if the Governor-General were present when she opened the High Court. As Sir David writes in his book, Head of State he so informed the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and draft orders of arrangements were prepared which provided a place for the Governor-General on the dais.

Malcolm Fraser appropriates the Governor- General’s place

It was only when the then Prime Minister, Mr Malcolm Fraser, saw the draft that he decided that the Governor-General should not be present: with the Governor-General out of the way, his place in the official procession next to the Duke of Edinburgh would be available for himself, the Prime Minister. Sir Zelman asked Sir David not to pursue the matter, but he was disappointed and very hurt. Far from being the application of a robust convention, the Governor-General’s absence was the result solely of Mr. Fraser desire to rank next to royalty.

Later Mr Fraser was to campign against the constitutional monarchy in the 1999 referendum, even appearing with Mr. EG Whitlam in a television advertisement based on the theme Mr Whitlam successfully used in the 1972 election, “It’s Time.” Sir David points out that when The Queen opened the Commonwealth Games in Brisbane in 1982 the Governor-General, Sir Ninian Stephen, was present and seated next to her, as did the Governor-General of Canada when The Queen opened the Commonwealth Games in Edmonton in 1978. “So much for Sir Anthony’s so-called robust convention, “observes Sir David. Sir David also cites the opening of the new Parliament House in 1988 to demonstrate the absence of any such convention, robust or not. A painting in Parliament House shows The Queen addressing the assembly in the Great Hall with the Governor-General on the dais. No doubt to the great embarrassment of Sir Anthony Mason, a press photograph at the time is fascinating. For it shows, sitting in the front row, none other than….. Sir Anthony Mason. When The Queen first came to Australia in 1954, she was received by Sir William Slim, the Governor-General, together with the Governor, the Prime Minister and the Premier. Nor did the Governor-General go into hiding during the tour. Sir William Slim was photographed with The Queen at a Garden Party in Canberra.[xxvi]

2020 Summit

In 2008, and in apparent ignorance of Sir David Smith’s refutation of the existence of any “robust convention” Professor Robert Manne and Dr Mark McKenna, in a video discussion posted to the website of The Monthly, accused constitutional monarchists of lying and of fraud when they say the Governor-General is Head of State.[xxvii] This interview was to promote the book “Dear Mr Rudd: Ideas for a Better Australia,” edited by Professor Manne and containing an opening chapter by Dr McKenna on the subject of changing Australia into some sort of republic. Of course, if constitutional monarchists are lying, diplomats, foreign governments, presidents, emperors, The Pope, international organizations, the Hawke-Keating governments, and the High Court, have fallen for this lie. They all believe that the Governor-General is Head of State or, in the case of the High Court, the Constitutional Head of the Commonwealth, the Governors being in its unanimous view, the Constitutional Heads of State. The principal argument Professor Manne and Dr. McKenna advance for their abuse is the same as that advanced by Sir Anthony Mason. They claimed that when The Queen is in Australia the Governor-General must disappear, and that this proves that Her Majesty is Head of State.

The academicians put their discovered “rule” in terms which would seem unusual for the learned world of academia. When The Queen comes to Australia, they say, “…the Governor-General has to push off.” Professor Manne and Dr McKenna have apparently neither read the decision of the High Court referred to above, the nor Sir David Smith’s refutation of the existence of any rule that the Governor-General must, as they so inelegantly put it ,“push off.” Vulgarity is of course no substitute for scholarship and research.[xxviii] Yet Professor Manne was appointed to the 2020 Summit.[xxix]

The Summit governance panel voted 98:1 to recommend Australia become a republic. Soon after, the Morgan Poll found that public support for Australia becoming a republic with an elected president had fallen to 45%, the lowest in 15 years. Among the young, (14-17) support had fallen to 23%. The Summit decided that the process to attain a republic should be a two stage process: “Stage 1: Ending ties with the UK while retaining the Governor-General’s titles and powers for five years. Stage 2: Identifying new models after extensive and broad consultation.” This opened the Summit to ridicule because all ties with the UK were terminated years ago.So ten days later, the recommendations now read: “Introduce an Australian republic via a two-stage process, with Stage 1 being a plebiscite on the principle that Australia becomes a republic and severs ties with the Crown and Stage 2 being a referendum on the model of a republic after extensive and broad consultation.”

The principal reason[xxx] for a preliminary plebiscite, rather than a referendum, is that the republicans fear a similar defeat as in 1999. There, despite strong media and political support, the referendum was lost nationally, in all states and 72% of electorates. The non-binding plebiscite will be a question only, without any detail.If the question suggests that only a republic can provide an Australian Head of State, in addition to material advanced in 1999, constitutional monarchists will be able point to the authoritative ruling of the High Court in 1907.

New arguements for constitutional change will have to be developed.

[i] David Flint, The Cane Toad Republic, Wakefield Press, 1999, chapter 2, pp 25-32

[ii] David Flint, Her Majesty at 80: Impeccable Service in an Indispensable Office, ACM, Sydney, 2006 pp

[iii] “Wall-to-wall republican governments?” 9 August, 2007, Australians for Constitutional Monarchy http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=982&Itemid=4 accessed 21 May, 2008

[iv] “Mr Beazley and His Plebiscites,” by Professor David Flint, AM, Upholding the Constitution:Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society [2001] Volume 13, Chapter 8, http://www.samuelgriffith.org.au/papers/html/volume13/v13chap8.htm accessed 27 May, 2008

[v] Approved by a majority of members of Parliament who had voted for the proposed constitutional change: Referendum ( Constitutional Alteration) Act, 1999

[vi] Australian Electoral Commission, Australian Referendums 1906-1999, DVD, 2000

[vii] Ibid. There was an initial dissent from one monarchist group, but they have since joined the monarchists’ consensus.[viii] “Special Report: “The republicans’ major campaign in 2006-” A Mate for Head of State” 13 August, 2006 Australians for Constitutional Monarchy http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=689&Itemid=24 accessed 9 May,2008

[ix] R v Governor of South Australia [1907] HCA 31; (1907) 4 CLR 1497 (8 August 1907); http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/HCA/1907/31.html accessed 9 May, 2008

[x] Constitution, section 71

[xi] Quick, J and Garran, R R, The Annotated Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia, Legal Books, Sydney, 19984, pp 135- 136

[xii] The Amalgamated Society of Engineers v The Adelaide Steamship Company Limited and Ors [1920] HCA 54; (1920) 28 CLR 129 (31 August 1920) http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/high_ct/28clr129.html, accessed 9 May, 2008

[xiii] Australian Dictionary of Biography On Line Edition, http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090294b.htm accessed 9 May, 2008

[xiv] Gould v Brown [1998] HCA 6; 193 CLR 346; 151 ALR 395; Re Wood [1988] HCA 22; (1988) 167 CLR 145; Re Cram; Ex parte NSW Colliery Proprietors’ Association Ltd [1987] HCA 28; (1987) 163 CLR 117; R v Toohey; Ex parte Northern Land Council [1981] HCA 74; (1981) 151 CLR 170

[xv] David Flint, The Cane Toad Republic, chapter 3 pp 37-48

[xvi] Imperial Conference, 1926, Summary of Proceedings, HMSO, 1926

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] “ State visit to Indonesia,” 22 February, 2008, http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1372&Itemid=4 accessed 9 May, 2008

[xix] Commonwealth Government Directory –The Official Guide Dec 95 – Feb 96, AGPS, Canberra, 1996

[xx] Flint, op cit p 41

[xxi]Sir David’s Smith, Head of State: the Governor-General, the Monarchy, the Republic and the Dismissal, Macleay Press, 2005, reviewed “Dispelling the myths:The Head of State…concluded,” 12 April, 2006 http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=603&Itemid=4%20 accessed 9 May, 2008

[xxii] Flint, The Cane toad Republict, p 93

[xxiii] Smith, op cit, pp109-112

[xxiv] “ Panic at Summit: judges resign,” 12 April, 2008, Australians for Constitutional Monarchy http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1413&Itemid=4 accessed 12 May,2008

[xxv] Smith, op cit p 190

[xxvi] JAMD. http://www.jamd.com/image/g/3326291?partner=Google&epmid=3 accessed 21 May, 2008

[xxvii] http://www.themonthly.com.au/tm/node/807 accessed 12 May,2008

[xxviii] A google search in Australia of “robust convention” linked to two ACM references to this issue: http://www.google.com.au/search?hl=en&rlz=1G1GGLQ_ENAU274&q=%22robust+convention%22&btnG=Search&meta=cr%3DcountryAU, accessed 29 June,2008

[xxix] “2020 Summit blunder: governance experts wrong,” 30 March, 2008, Australians for Constitutional Monarchy http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1400&Itemid=4 accessed 22 May, 2008

[xxx] See also the suggested eight advantages, supra